Vipassana meditation originates from the Theravada Buddhist tradition. Buddhism today has two major branches: Mahayana and Theravada.

The word Vipassana comes from two parts: ‘Vi’ meaning “in various ways” and ‘Passana’ meaning “seeing.” Together, Vipassana means “seeing things in various ways” or “insightful observation.”

Vipassana helps you see things as they truly are by gradually freeing the mind from mental impurities. With practice, you begin to notice how thoughts, emotions, and physical sensations arise and pass away. What once appeared permanent or desirable is observed to be constantly changing.

This understanding allows you to approach life with less agitation and more tranquility.

No. Vipassana is not a religious practice—it is a method of observing and understanding yourself. You simply observe what arises in your body and mind at the present moment.

Vipassana is for anyone seeking to heal the mind from defilements like greed, hatred, and delusion. Since we all experience these, everyone can benefit from this practice, regardless of age or background.

There is no fixed time. Mental impurities are almost always present, so Vipassana is helpful anytime during the day.

Just as we eat and care for our bodies every day, our minds need to be cleansed daily. Practicing in the morning hours and before going to bed are both beneficial. But you may practise any time.

It can be both easy and challenging. It is not easy to control the mind, which naturally wanders. However, Vipassana is simple to practice: there are no complex rituals or teachings to learn. You simply sit, observe yourself, and focus on the object of meditation.

To fully benefit from the practice, you need:

No special equipment is required. A quiet place to sit is enough. Cushions, benches, or chairs can be used for comfort, but avoid over-indulgence in comfort, which may lead to drowsiness.

While sitting on the floor is traditional, you may meditate in any comfortable position. Vipassana can be practiced in any posture: sitting, standing, walking, or lying down. What matters is mindfulness, not one’s position.

It is usually better to keep your eyes closed, but you may leave them open if that is less distracting. If your eyes are open, simply note “looking” whenever you focus on something. The important thing is to have good concentration.

There is no strict rule. Common positions are:

Choose whichever is comfortable.

Start with a duration that is comfortable for you—15 or 30 minutes, gradually increasing to an hour or more. If you can meditate longer without discomfort, you may extend it to two or three hours.

Learning Vipassana is much easier with the guidance of an experienced teacher. A teacher can offer clear feedback, help correct misunderstandings, and support you when difficulties arise.

While books can be helpful, they cannot fully replace a teacher to ensure proper understanding and practice.

Yes. Mindfulness can be applied to all daily activities, like walking, working, and solving problems. Regular practice helps you respond to life more calmly and effectively.

Vipassana meditation originates from the Theravada Buddhist tradition. Buddhism today has two major branches: Mahayana and Theravada. Mahayana spread to Northern Asian countries like Tibet, China, and Japan, while Theravada remained in Southern Asia, spreading to countries such as Sri Lanka, Myanmar (Burma), Thailand, Cambodia, and Laos.

The word Vipassana comes from two parts: ‘Vi’ meaning “in various ways” and ‘Passana’ meaning “seeing.” Together, Vipassana means “seeing things in various ways” or “insightful observation.”

The ultimate goal of Vipassana is to completely eradicate mental impurities from the mind. Along the way, it brings peace, tranquility, and the ability to accept things as they are. By practicing, you will observe how mental and physical phenomena arise and pass away, helping you understand your mind and body more clearly. This clarity allows you to respond to situations calmly and positively.

Vipassana is for anyone seeking to heal the mind from mental defilements like greed, hatred, and delusion. Since we all experience these “mental illnesses,” everyone can benefit from this practice.

There is no fixed time. Mental impurities are always present, so Vipassana can be practiced anytime—morning, during the day, or before bed. It can also be practiced at any age.

No. Vipassana is not a religious practice—it is a scientific method of observing and understanding yourself. You simply observe what arises in your body and mind at the present moment.

It can be both easy and challenging. It is not easy to control the mind, which naturally wanders. However, Vipassana is simple to practice: there are no complex rituals or teachings to learn. You just sit, observe yourself, and focus on the object of meditation.

You need:

With these qualities, you can benefit fully from the practice.

No special equipment is required. A quiet place to sit is enough. Cushions, benches, or chairs can be used for comfort, but avoid over-indulgence in comfort, which may lead to drowsiness.

Vipassana can be practiced in any posture: sitting, standing, walking, or lying down. Awareness is more important than posture.

No. While sitting on the floor is traditional, you may sit in any comfortable position. What matters is awareness, not the posture.

It is usually better to keep your eyes closed, but you may leave them open if that is less distracting. If your eyes are open, simply note “looking” whenever you focus on something.

There is no strict rule. Common positions are:

Choose whichever is comfortable.

Start with a duration that is comfortable for you—15 or 30 minutes, gradually increasing to an hour or more. If you can meditate longer without discomfort, you may extend the time to two or three hours.

Daily practice is highly recommended. Just as we eat and care for our bodies every day, we should cleanse the mind daily. Morning is ideal for a fresh mind, and evening practice before bed is also beneficial.

Yes, a competent teacher is important for guidance, corrections, and encouragement. While books can help, a teacher ensures proper understanding and practice.

Yes. Mindfulness can be applied to all daily activities, like walking, working, and solving problems. Regular practice helps you respond to life more calmly and effectively.

A retreat is an opportunity to deepen practice in a supportive environment with guidance from an experienced teacher. All activities—walking, eating, sitting—become objects of meditation.

A typical retreat includes:

Retreats can last from one day to several weeks.

Retreats provide intensive practice, improving concentration and quieting the mind. Strong concentration is essential for developing insight and understanding the true nature of reality.

No. Sit comfortably in any posture

Start 15–30 minutes, gradually increasing to 1 hour or more

Yes. Bring mindfulness to walking, working, and problem-solving

We greatly appreciate and welcome your kind generosity to help support the continuous development of the centre.

© 2026 PSMC. All rights reserved.

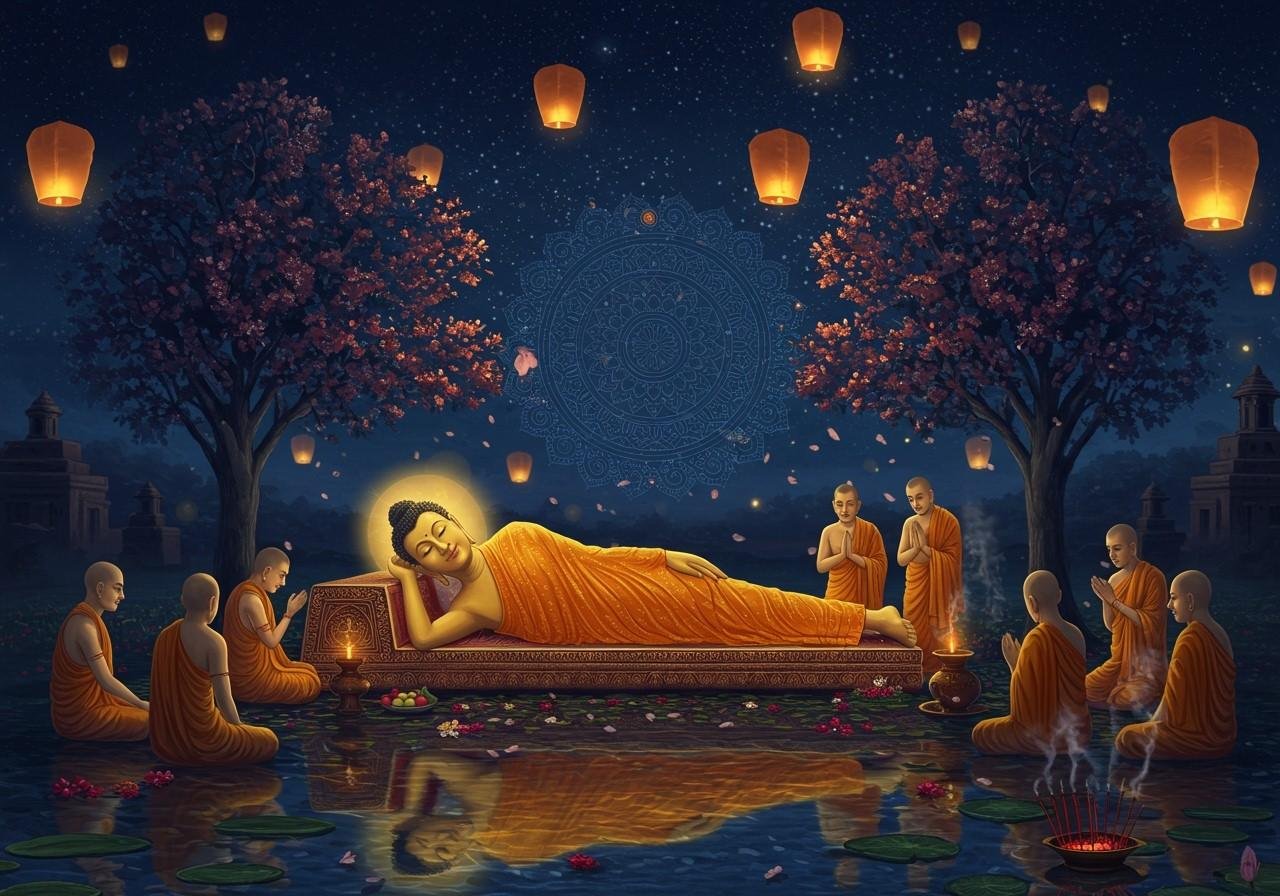

At the age of 80, the Buddha sensed his life was nearing its end. He continued teaching until his final moments, offering guidance to his disciples on maintaining harmony and staying committed to the path.

The Buddha passed away peacefully in Kushinagar, entering Parinibbana—the final liberation from the cycle of birth and death. His teachings, preserved for over 2,500 years, have since spread throughout the world and remain a source of wisdom and transformation today.

The Buddha’s life demonstrates that profound inner peace and liberation are attainable through understanding, ethical living, and mindfulness.

For the next 45 years, the Buddha travelled widely across northern India, sharing his teachings with anyone eager to learn—monks, nuns, farmers, royalty, merchants, and people from all walks of life. His teachings emphasised wisdom, moral conduct, mindfulness, compassion, and the potential for every being to awaken.

He established monastic communities, guided thousands of followers, and offered practical teachings that continue to resonate today. The Buddha taught in a simple and accessible manner, focusing on understanding the mind, cultivating virtue, and realising inner peace.

Soon after his enlightenment, the Buddha travelled to Sarnath, where he delivered his first discourse to five former companions. This teaching, known as the Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta, introduced the Four Noble Truths and the Noble Eightfold Path. With this, the Sangha—the community of monks—was born, marking the beginning of the spread of the Dhamma.

Siddhartha eventually settled beneath a fig tree in Bodh Gaya, vowing not to rise until he discovered the truth. After a long night of deep meditation, he awakened to a complete understanding of reality, the nature of suffering, and the path to liberation.

At this moment, Siddhartha Gautama became the Buddha—“The Awakened One.”

At 29, Siddhartha made a courageous and transformative decision. Leaving behind his royal life, his family, and all worldly luxuries, he embraced the life of a seeker. This departure, known as the Great Renunciation, was the beginning of his spiritual journey.

He travelled across northern India studying with respected teachers and practising intense forms of meditation and asceticism. Though he mastered these methods, they did not bring the liberation he sought. Realising that extreme self-denial was not the answer, he abandoned harsh austerities and turned toward a balanced approach—a path later called the Middle Way.

Although Siddhartha grew up sheltered, a series of life-changing encounters expanded his understanding of the human condition. While visiting the city beyond the palace walls, he saw an elderly person, a sick person, a corpse, and finally a serene wandering monk. These four sights deeply affected him. They revealed the inescapable truths of aging, illness, and death—and showed him that a spiritual path might offer liberation from suffering.

These moments awakened a profound inner questioning that could not be silenced:

What is the cause of suffering, and is there a path to true peace?

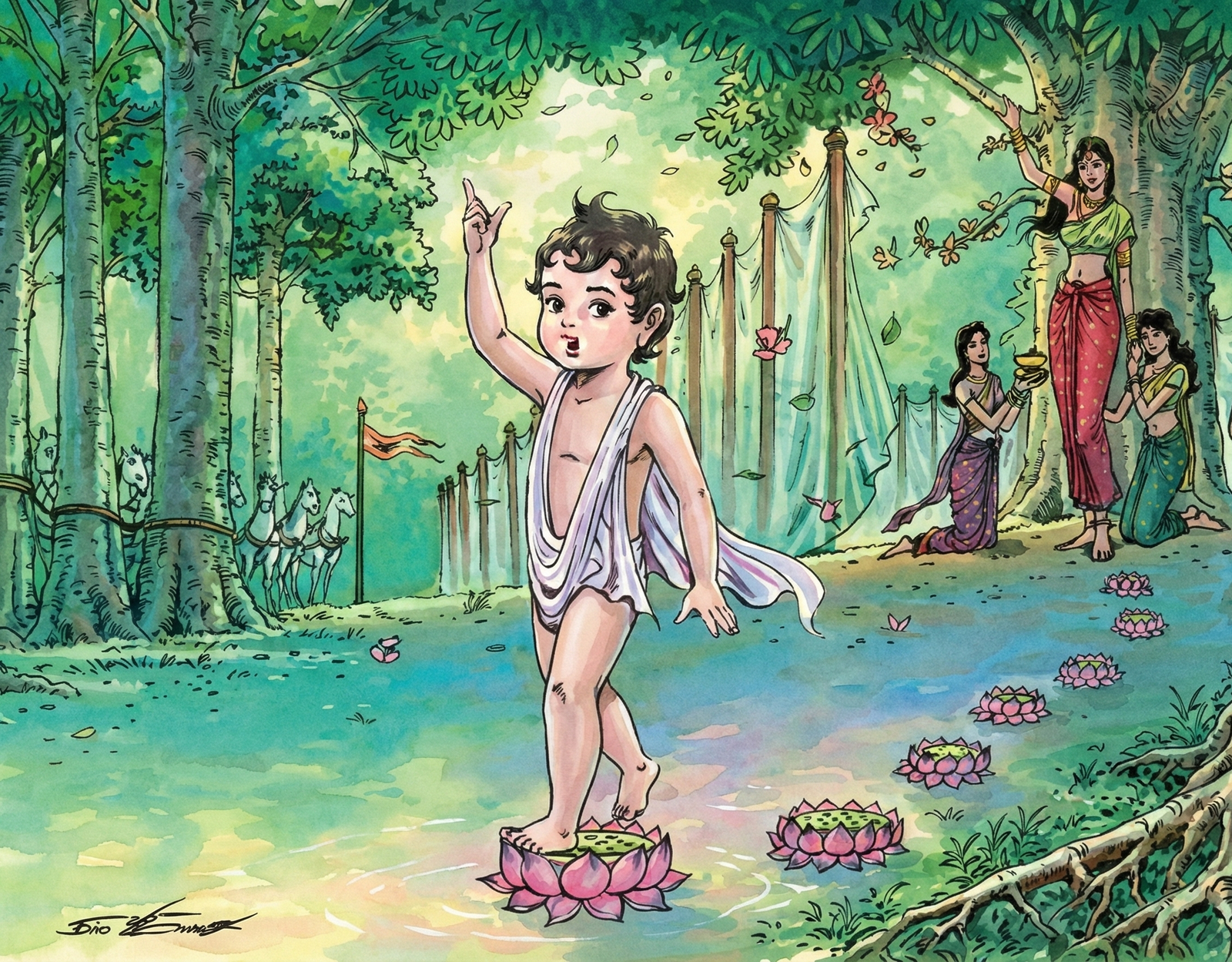

Siddhartha Gautama, who would later become the Buddha, was born around 563 BCE in Lumbini, a region that is now part of Nepal. He was born into the royal Shakya clan to King Suddhodana and Queen Maya. Tradition describes his birth as peaceful and auspicious. After his mother’s passing one week later, Siddhartha was lovingly raised by his aunt, Queen Mahapajapati.

Growing up in the city of Kapilavatthu, Siddhartha enjoyed a privileged and protected life. His father, wishing to shield him from the hardships and uncertainties of the world, ensured he received the finest education, martial training, and a life surrounded by comfort. At the age of sixteen, Siddhartha married Princess Yasodhara, and together they had a son named Rahula.